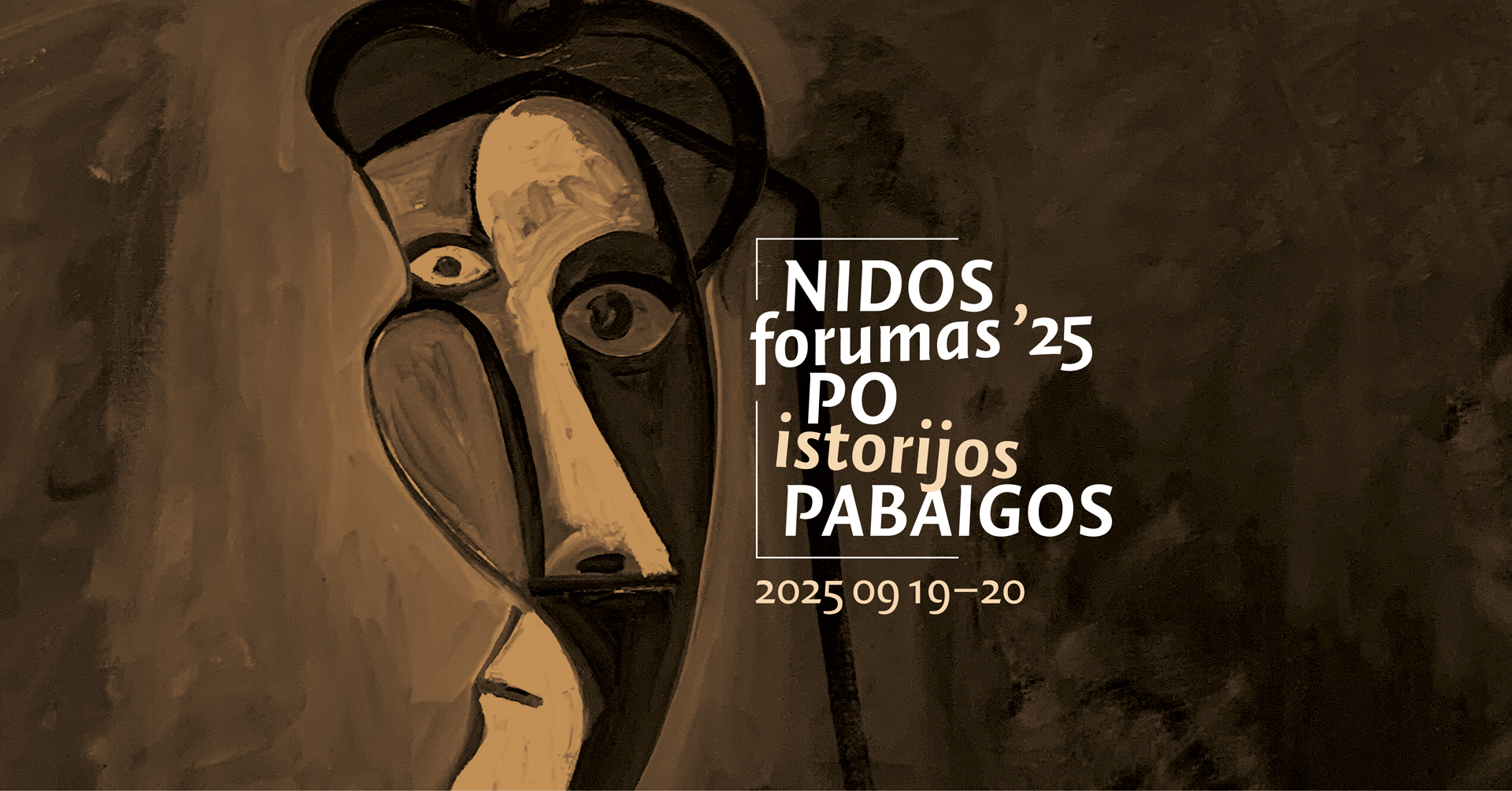

Nida Forum 2025

A new world order is emerging.

How this sentence bores me! By now it can be heard and read every single day. What is wrong with me? Do I lack understanding and empathy for the millions upon millions of people to whom this fact causes enormous fear? Above all, fear of loss and decline, insecurity, as well as nostalgia in its aggressive form, namely a longing for an uncompromising and, if necessary, brutal restoration of old ideas of order. These fears and twisted longings are indeed leading to shifts, even upheavals, in the domestic and foreign policies of countless countries, to new alliances and new lines of conflict.

And that bores me? I don’t take it seriously?

On the contrary, I do take it seriously. What bores me, however, is the way this development is commented on and discussed: on the one hand forgetful of history, as if there were no historical experiences and lessons to which we might now turn, and on the other hand completely devoid of imagination regarding a desirable future, the possibilities that are opening up and practically forcing themselves upon us—in short, regarding the history we must now make.

What if we look at the novelty of this “new world order” already from a historical perspective? Do we see a fundamental change in the system, in how the world is divided up and how powers attempt to assert their claims over parts of it? No. Essentially, the much-invoked new world order is merely a continuation of the present with a certain rebalancing of the so-called global players’ options. If, in a game of chess, we agree and accept that the rook is less important and henceforth may move only one square at a time, it is still chess to those watching intently—and the rook would confidently declare that it can now do exactly what the king does.

However differently we may assess and judge historical processes and events, there is one fact on which everyone must agree: everything that had a beginning in history also eventually had an end. This is how we may sum up the entire history of humankind, and this is how we should also look at present developments. Do we really need to be reminded that the ancient slave-owning society no longer exists today, that the Roman Empire, feudalism and absolutism, the divine right of kings, and so on, have vanished?

Or can you imagine that the city of Ulaanbaatar was once the center of the world, when Mongol domination spanned nearly the entire Eurasian continent—from China across Persia and Iraq to Russia? People back then could not imagine that Ulaanbaatar would one day become a desolate city in a remote corner of the world.

You can be sure that people living in any given era could not imagine that what was familiar to them would ever come to an end. And yet it did.

Imagine a slave and his wife going to Cleisthenes, the founder of Athenian democracy, often referred to as the cradle of our democracy, and daring to ask: “Honored Cleisthenes, can you imagine a democracy without slaves, but with women?” At best, Cleisthenes would have burst out laughing. He could not have imagined it.

Imagine a serf in the heyday of medieval feudalism going to his lord and humbly saying that, according to the teachings of Christ, the concept of serfdom was entirely wrong and anything but divinely ordained. Do you think the lord would have considered that the man might be right, and that therefore the system would one day perish? That he would have said, “Good man, let’s drink a cup of wine to that”? Certainly not. The system was designed to last forever, and when it did end, its beneficiaries must have been utterly confused, astonished, terrified—and then highly aggressive.

Let us return to the present. Or rather, to the becoming of our present. Since the time of our great-grandparents (and most of us know family stories from that span of time), every generation has experienced the end of one world order and the birth of a new one—every generation. The First World War destroyed four empires; afterwards, the world was different. Then the helplessness of the small nation-states, so fiercely fought for and founded with euphoria, became evident—they turned into pawns in the struggle for a new world order, promised by the League of Nations, which soon failed and made way for yet another order. In the Second World War, the USA and the Soviet Union rose to great power status, dividing the world between them—a new world order that ended in 1989 (something unimaginable just weeks before the fall of the Berlin Wall), after which China rose to great-power status—yet another new order!

So if ever there were a message without news value, it is this: a new world order is emerging. In every generation! But—and this is important to understand—these were always world orders born of the rivalry between nations.

A true novelty would be if we openly discussed which order of the world and which political organization of our social life we would find desirable in the spirit of the progress of freedom—something genuinely new—and how we might create it, and with what means. The question is this: do we want to endure a new world order, or do we want to shape it? Do we want to merely glean from the media what is happening through uncontrolled dynamics, driven by powers and people beyond our influence, and what we must fear? Or do we want to become subjects of history?

Let us first clarify the premises. The emergence of the new world order, which makes us so nervous today, is in truth a zombie dance of history—namely, a struggle of great nations for global supremacy. Why a zombie dance? Because globalization has long since overcome the very idea of the nation. This is an important premise for further discussion.

What is globalization? A dynamic economic development, fixated on perpetual growth and expansion, which has led to multinational corporations, has shattered national borders, ignored or subordinated the sovereignty of states to its own interests, created laws beyond national rule of law, and made national politics subject to its coercion—in short: it has destroyed the very foundation of the idea of the nation and of the nation’s legitimacy. International division of labor in production, supply chains, financial flows—these have long been transnational. Nation belongs to the 19th century, at best it is vintage.

The only ones who have not yet understood this are the great nations, who believe that globalization is merely another dynamic over which they must gain national control in order to achieve global dominance—even at the expense of their own populations. Politically, they still tick according to the tinny mechanics of the 19th century: it is about territorial expansion, exclusive access to resources, spheres of political influence; it is about so-called alliance policies that demand subjugation, for example through the installation of puppet governments or the support of rogue states—and all of this, ultimately, by military means. And we have not even spoken yet of the utterly outdated notions of an ethnically and linguistically pure nation, cleansed of people of other origins, languages, and religions—in the face of global migration and refugee movements.

It is understandable that in a time of great transformational crises, for very many people the world, which objectively is becoming more and more interconnected, subjectively seems to be falling apart—into a world “out there,” from which threats come, and into the world of their immediate living space, their country, from which they expect protection and the defense of their way of life and their life opportunities. This is the hour of the right-wing populists. They promise to restore and defend the order and security of their own nation against the assaults of a chaotic and dangerous world.

But nationalists cannot possibly fulfill their promises. For none of the great challenges that must be met—from migration flows to climate protection, from the transformational crises of the economy to international financial crises, the internet, cyber warfare, artificial intelligence—absolutely nothing of importance for life in prosperity, freedom, stable democracy, and security can be mastered within the borders of a single nation, least of all small nations.

Thus the nationalists must fail. How will voters react? They will say: this national politician to whom we entrusted our confidence was not consistent enough; we need a more hardline nationalist government. Such a government will, for a time, attempt to provide surrogate satisfactions through symbolic politics and culture wars, but it too will fail, because all of the challenges are already transnational. And so the call will arise for a harsher, uncompromising leader—one who will not let himself be hindered by the limitations and restraints of power as democracy prescribes. This is the path into fascism.

While one may understand this dynamic, it would be utterly incomprehensible and unacceptable to accept it.

Let us take a brief look back. Europe after 1945: States that shortly before had still been enemies, devastated by nationalist wars and crimes, drew a political consequence from this collapse. With the founding of the European Coal and Steel Community, which later developed into today’s EU, they consciously entered into a post-national process to overcome the aggressor responsible for the greatest crimes in human history—the aggressor was called nationalism.

The idea was to intertwine national economies so closely that no participating state could take action against another without harming itself, thus de-nationalizing and generalizing the common good, under the control of supranational institutions, which were also given the task of further developing this process. International organizations had existed before—they failed, like the League of Nations, or continue to fail, like the UN. Europe is the first continent to have created supranational institutions, and that is something entirely different and far-reaching. I claim that here we see the real epochal break, even if it progresses gradually.

This process has carried surprisingly far, considering how unimaginable it must initially have been for the majority of people in Europe, what was then gradually implemented. Who could have imagined that France, shortly after finally defeating and expelling the German occupiers, would cede sovereignty rights to a joint authority with the Germans? Who could have imagined that the Germans would give up their extremely fetishized Deutsche Mark in favor of a European common currency? Who in the 1950s could have imagined that one day the European state borders within the Union would fall, granting freedom of travel and residence? And yet, all of that—and much more—has come to pass.

The European Charter of Fundamental Rights has constitutional status in the EU, in contrast to the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which is merely a recommendation and has not even been ratified by many states, from the USA to the Vatican. That is the difference between international agreements and supranational design. This is a step forward in the history of humankind that, in my opinion, is more significant than the first step of a human being on the moon.

The idea of dissolving European nations into a political community that, on the basis of human rights, produces common law valid for all, wherever they live and work—or want to live and work—in Europe, giving them legal certainty and guaranteeing all freedoms: this idea will, after the history that preceded it, one day surely be described by historians as the most significant revolution on this continent.

The idea. And the first steps. And then? Let us return to the present situation, and let us recall this simple historical-philosophical truth: everything in history that has had a beginning will also have an end. We find ourselves today in a world-historical moment in which the idea and the claim of nation-state politics of interest have objectively become obsolete and are defended only by three or four of the largest nations with the greatest military power. We can see that all the promises of a nation regarding prosperity, freedom, and the rule of law have become fictions, producing a social frustration for which all those who do not belong to the self-defined community must pay the price.

The European community project did not begin in 1951 as a response to the challenges of globalization (the term globalization was only popularized in 1983 by the American economist Theodore Levitt!), but rather as a response to the experiences of the first half of the 20th century. I find this truly interesting: the idea that arose at that time as a reaction to historical experiences, as a consequence of what had come before, today proves to be the only one fit for the future—namely, to consciously shape a post-national world.

In other words: in terms of shaping globalization, the EU would have the greatest expertise. For precisely what is now necessary, the European project—unique in the world—has already been attempting for more than seventy years.

So if we are truly to discuss the emergence of a new world order, then we must assume this: the new world order will be the post-national world, and in the present historical phase of “no longer, not yet,” the European Union is the avant-garde.

Or would be. I asked: what happened after the first steps? Ideas live initially through the people who set them into the world and persistently strive to carry them forward step by step. But after more than seventy years, it must sadly be said, those people—the founders of the European community project and also the architects of the Union’s last great achievements—are all dead. Politicians such as François Mitterrand or Helmut Kohl, for example, still knew that their domestic policies always had to be European policies as well. A Commission president like Jacques Delors still knew what the task of the Commission was: namely, to carry the process of integration forward step by step, and with each small step to plan and enable the next.

What they left behind is a half-way Union, standing or stuck halfway, because the next generation had not shared their experiences. They found the Union as it was, took it for granted, and did not understand that it needed further development. Their experience was and is simply this: they are elected nationally, they came into positions of power through national elections, and now must defend “national interests” within the EU framework they found in place. Whatever that is supposed to mean. What is in the interest of an Austrian should surely also be in the interest of a German, a Portuguese, a Greek, a Czech, and so on—unless one defines national interests this way: national interests are the interests of national elites.

In any case, what had been achieved so far came into conflict and contradiction with the old systems that were defended, although they ought reasonably to have been overcome. We have a common market, in essence already an aggregated European economy, but we still account on the basis of national economies. Thus, for example, goods produced in Germany and consumed in Greece appear in the German export statistics and in Greece’s public debt. Then Greeks are punished by Germans for consuming German goods—which, in fact, was exactly what German industry wanted.

We have a common currency but no common financial policy, which leads to the grotesque situation that, depending on where we live, we have different levels of inflation, entirely different national positions on investment or debt, or a surreal diversity of state financial benefits for citizens. We have a European Parliament, a people’s representation—the first supranational representation in history—but in European elections we can only vote for national lists. This, of course, produces the absurdity that many citizens, believing these elections to be about representing national interests and not about common law, vote for nationalists, who then do nothing but obstruct Parliament.

We have freedom of establishment and employment within the EU, yet in the countries where we work and pay taxes, we cannot vote unless we have that country’s passport. We can only vote in the country where we no longer live, no longer work, and no longer pay taxes. We call the Union democratic, but in reality it consists of twenty-seven entirely different democratic systems, whose only common feature is that holders of national passports may vote nationally. Within the Union there are democratic republics and constitutional monarchies, centralized and federal democracies, systems with two votes or with just one, or with the option of a preference vote, systems with plebiscitary democratic elements or strictly representative democracies, with majority voting or proportional voting. And the very arithmetic of national elections, the national system of seat distribution, leads to an election result that would come out completely differently under another European state’s arithmetic—so what, then, is objectively the “will of the European voter”?

In some countries one can vote at sixteen, in others only at eighteen—how, then, are sixteen- to eighteen-year-olds in those countries democratically represented? The development of a common, European, that is, post-national democracy would be indispensable if Europe wishes to call itself democratic in the future. But in Europe’s realm of imagination, the idea does not hold. Because among the political elites, the idea is no longer explained and defended.

Thus, from the contradictions between the stalled post-national development and the rigid defense of national sovereignty arise precisely the helplessness and lack of perspective—both of the European institutions and of the national governments—that are generally perceived as “the crisis.”

The crisis is now devouring the soul of the Union. The European Union, as we know, was from the beginning conceived as a peace project. Reconciliation, peace—on that, the members of the Union, to our great fortune, could agree. But of course not on a common peace and security policy. Once again, the typical contradiction: peace of the Union in lofty Sunday speeches, but peace and security policy pursued nationally. I imagine Putin asking: “How many divisions does the European idea of peace have?”

When I wrote about ten years ago that Europe must also be able to defend peace, I reaped a shitstorm. Was I perhaps advocating military armament, preparing for war? The defensive pacifist in me was beaten down by militant national pacifists.

Now, threatened by Putin’s aggression, this actually simple thought—that a peace project must also be able to defend its peace—has become not only mainstream, it has led to decisions. And again, they are wrong. The Commission releases billions for financing defense—but each member state is to arm itself on its own. Even if a French bullet does not fit into a German assault rifle—no matter, each for himself. Austrian armament will be neither a relevant factor for a common European defense policy, nor for the solipsistic defense of neutrality. No matter—Austria is supposed to reduce its budget deficit while increasing debt for weapons systems.

And the national heads of state tremble with nervousness because they may no longer be able to rely on U.S. help—instead of asking themselves why, for so long, they had found it so self-evident that a sovereign, democratic Europe should be under U.S. military command. They regard the defense or restoration of what they had long believed they could rely on as pragmatism, and they even submit to Trump’s kiss-my-ass demands—instead of asking how, under the given circumstances, the real necessity, namely a free, sovereign, post-national Europe, could pragmatically be developed as a model for a world in which national sovereignty is demonstrably withering away.

The future of the world begins in Europe—if we make clear to ourselves that it is not political pragmatism to somehow adapt to the dynamics of the time, to make ourselves “fit” for them, as is often said. No, that is not pragmatism, but submission.

How do we see today those politicians who, at the end of the 1920s, were pragmatists in this sense and said: the trend is clearly towards fascism in Europe, so now we must make ourselves fit for fascism? Do you find this “pragmatism” reasonable in retrospect?

Or: imagine workers in the time of Manchester capitalism, earning starvation wages, families barely making ends meet, even though the children were working in the factories. Would you today call them pragmatists if they had said they needed to make themselves “fit” for hunger? They fought, against enormous resistance, for better wages, for the eight-hour day, for the prohibition of child labor—and that is what I call pragmatism, confirmed by the future.

The force of factual blockades must not become normative for us; unfavorable balances of power must not define the limits of the possible. Especially since the new world order emerging in Europe has already created facts on which we can build. I have already said that in terms of post-national community policy, Europe is avant-garde. What would be forward-looking is to combine this with self-confidence, and with the insight that harmonization must go further. For what is experienced in Europe as crisis is nothing other than the consequence of the unproductive contradiction between community policy and re-nationalization, which blocks all progress.

I have said: everything in history that has had a beginning has also had an end. This is how we may summarize the entire history of humankind, and this is how we should view present developments. That means now: we must ask ourselves, what is coming to an end when we once again speak of the emergence of a new world order—and what, in historical terms, is in the process of being born?

We might conclude this: if, in a world order defined by nation-states, the balance of power among nations shifts, that is not a new world order. The truly new world order emerges through the gradual disempowerment of nation-states.

I have already said: globalization means the destruction of the sovereignty of nation-states, and the EU means—at least in principle—the shaping of a post-national world. I do not believe there is anyone capable of arguing convincingly that a world politically organized into nation-states is the end of history.

That today the largest and militarily strongest nation-states aspire, in this situation, to become world hegemons does not disprove this finding. Supposedly, the fingernails of the dead continue to grow. Even if they grow into claws, they are the claws of the objectively dead. They can injure, they can shock—but history continues: the history of those who organize life.

It is a long, contradictory process, whose end we will not live to see, but in which we are entangled, and in which we must act.

That is the question I wanted to put to you: how do we deal with this, what are the guiding stars of our actions? I know nothing better than to defend the reason of the European idea. The defense of the idea requires criticism. We must not gloss things over if we want to do them well. We must criticize the unproductive contradictions of the Union. We must recall history and its lessons. We must dream, and in so doing ground our pragmatism. We must remind ourselves again and again that it is about community politics, about a common legal order—enforceable, defensible.

This is truly about a new world order. A world order for which Europe will stand as a model—not as a hegemon.

If you think such a thing cannot exist—listen to Cleisthenes laughing.

Remember how long it has always taken before epochal breaks became visible!

When we look back at history, we always admire and honor those who recognized what social and political progress was coming into being and had to come, and who worked for it, even when the old powers still seemed mighty. That is how we should one day be looked back upon.

Our grandchildren will be grateful!