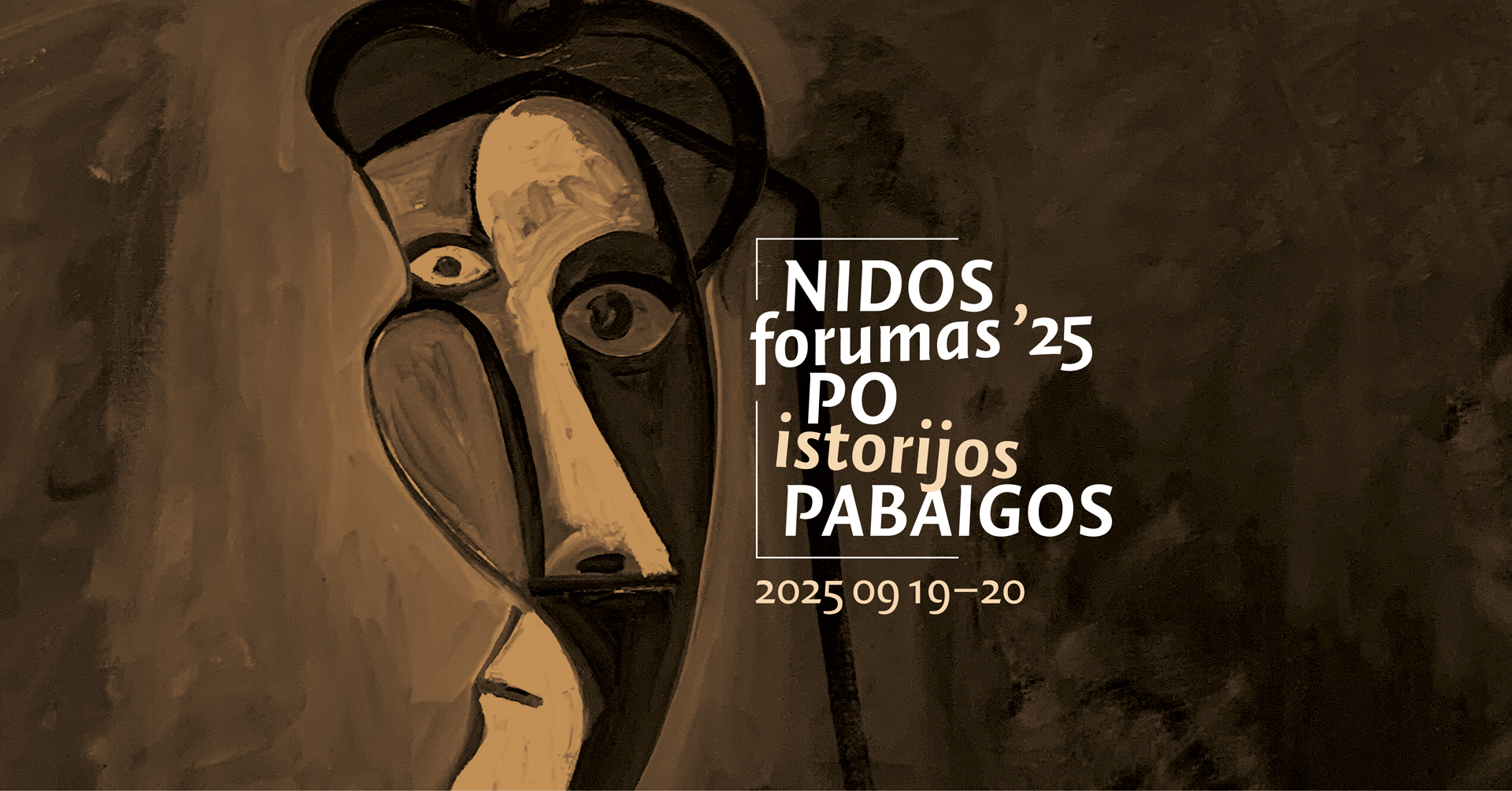

20-09-2025 Nida Forum, History Museum of Curonian Spit

My grandmother was born in 1927 on a remote farmstead in eastern Slovakia. At that time, the First Czechoslovak Republic was less than nine years old.

In 1939, when my grandmother was twelve, World War II broke out and interwar Czechoslovakia ceased to exist. In the Czech lands, the Protectorate was established, while she lived in the fascist Slovak State.

When the conflict ended in 1945, a brief period of democratic postwar Czechoslovakia followed. However, in February 1948, a communist coup occurred, and in August 1968, Warsaw Pact troops intervened against an alleged counterrevolution in Czechoslovakia.

In November 1989, the Velvet Revolution took place, and in January 1993, independent Slovakia was established, which joined the European Union in 2004. When my grandmother died in the summer of 2011, independent and democratic Slovakia was a firm part of the Western world.

She never traveled much, although she once flew to Bulgaria for a summer holiday. Otherwise, she spent her entire life in a small area between Spišská Nová Ves and Poprad, two towns in eastern Slovakia about twenty kilometers apart.

She basically never really moved, but still she lived in six different states: democratic Czechoslovakia, the Slovak State, democratic postwar Czechoslovakia, communist Czechoslovakia, democratic Czechoslovakia once again, and eventually independent Slovakia.

Similarly, she lived under four different regimes: a democracy, a fascist wartime state, a communist dictatorship, and a democracy again.

The end of history: again?

In this article, my grandmother is not the main character, but she is a good example of what life in this region entails.

What is this region? I believe it is Central and Eastern Europe along with the Baltics. A region situated between Russia and the Western world, with these two forces shaping its fate. It is the area we call post-communist Europe.

And what does life here mean? Well, constant change. One might wish for some stability, but here things just keep changing: borders are redrawn (often followed by population transfers), political systems change (and sometimes history itself is rewritten).

The longest-lasting political entity here was communist Czechoslovakia, which lasted four decades; independent Slovakia is now in its fourth decade. This is a country where history just keeps ending: at least eight times in the last hundred years, each time feeling like it was forever.

The question today is whether we find ourselves at the end of history—and what comes next. Someone like me, with this historical experience, might ask: Are we at the end of history today? Again? And if so, how to prevent going in an undesirable direction?

A delicate situation

The first “end of history” came right after World War I, in 1918. That’s when Austria-Hungary dissolved, and today’s Slovakia became part of interwar Czechoslovakia, which inherited a diverse ethnic composition: besides Czechs and Slovaks, there were also significant minorities of Rusyns, Ukrainians, Hungarians, and Germans. Also, Hungary and Germany always considered this arrangement temporary at best and made no secret of this.

We tend to mythologize the First Czechoslovak Republic as a liberal democracy in the heart of Europe heading towards WWII; yet it faced many problems.

Due to the Geat Depression, Czechoslovakia faced real economic difficulties and social unrest (harshly suppressed). The Communist Party, openly taking orders from Moscow, was a threat (also suppressed). Moreover, the loyalty of many citizens to their own country could be questioned—and this applied not only to Hungarians and Germans, but increasingly some Slovaks as well.

Interwar Czechoslovakia was well aware of this delicate situation and tried to secure itself by signing a series of defensive treaties and building a defensive line on the German border.

It turned out to be in vain: when those defensive treaties mattered most, they no longer applied; the defensive line was also absolete because after the Munich Agreement, Czechoslovakia lost that territory and was left practically defenseless.

Interwar Czechoslovakia ceased to exist shortly before its twentieth birthday, marking the second end of history.

Life was not bad (well, depending on whom you ask)

The Slovak State was a puppet regime of Nazi Germany. Yet, it was also the first independent state entity on Slovak territory—well, at least to some extent. Its rulers, led by Catholic priest Jozef Tiso, acted as if it was to last forever.

During its brief existence, the Slovak State deported most of its Jewish population to concentration camps, also paying the Third Reich for the deportations. Few returned, and even survivors were often unwelcome as locals had taken over their property.

True nostalgia for it is marginal in society, but there has also been no real reckoning with its legacy—we moved on, but the wounds remain. Some defend the wartime state by saying: “Yes, there were tragedies (it was war, after all), but we finally had our own state and life was not bad.” (A cynic might say: it depends on whom you ask.)

In August 1944, the Slovak National Uprising broke out. Though unsuccessful, it is one of the bright moments in Slovak history. Less than a year later, WWII ended and the Slovak State, which was supposed to last forever, collapsed like a house of cards. Those leaders who didn’t escape were executed, though many did manage to flee.

Thus came another end of history—but even that wasn’t enough. Postwar democratic Czechoslovakia was short-lived, and in 1948, during the so-called “Victorious February,” the Communist Party took power. This was the fourth end of history in thirty years and a very serious one as well.

Two perspectives

As Czechs and Slovaks, we like to say that before WWII, we were the seventh or eighth richest country in the world—and definitely richer than Austria. It makes us feel good.

As Slovaks, we also like to say we didn’t vote for the Communists. It was the Czechs. This makes us feel good too. And it’s true: in the last democratic election in 1947, the Communists won over 43% of the vote in Czech lands and finished first; in Slovakia, the Democratic Party won with 62%.

The first phase of the communist regime lasted for two decades. At the end of the 1960s, Alexander Dubček’s government tried “communism with a human face,” also called the Prague Spring. The subsequent Warsaw Pact invasion is also called “fraternal assistance.”

1968 was crucial: A quarter of a century later, when Slovakia beat Russia in the 2002 Ice Hockey World Championship final and were crowned champions for the first and only time, my mother shouted at the TV, “That’s for ’68, you bastards!”

The Warsaw Pact invasion was a huge blow to my parents. For many, it confirmed that the communist regime was not capable of surviving on its own. But that didn’t mean it ended.

After the 1968 invasion, Soviet troops remained in Czechoslovakia. A period called normalization followed, interpreted differently depending on whom you ask. Czechs say it was a time of stagnation and inertia; Slovaks might say it was a period of unprecedented development, construction, and urbanization—and both are unfortunately true.

The Russians are leaving

I have two memories of the Velvet Revolution in 1989.

The first is of me wanting to watch a children’s TV show but my parents kept switching to the news. I understood something was happening. I also understood what exactly it was. My grandmother’s second husband came from a wealthy Moravian industrial family. They lost everything after the communist takeover, so he hated them with a passion and always told me this would end one day. It did, but he didn’t live to see the revolution; he died a few months before.

The second memory is from early 1990, when I was a small child in a hospital in Poprad. Next to the hospital was the main road heading east, towards the Soviet Union. I couldn’t sleep because tanks and military vehicles rumbled by all night. The Russians—because even though these were Warsaw Pact and later Soviet troops, we always called them Russians—were leaving.

This was another end of history: the Russians were gone forever, communism ended forever, Czechoslovakia was supposed to be democratic. Forever. The problem was that soon there was no Czechoslovakia and almost no democracy, too.

Czechoslovakia began to break up almost immediately after communism’s fall, against the will of its citizens. The split had no popular support; a referendum was planned but never held. Still, it was the end, and although almost no one wanted it at the time, today, pretty much everyone will tell you it was for the best.

Independent Slovakia officially came into existence on January 1, 1993: finally, we really did have our own state. But again, a problem arose: the split was orchestrated by Václav Klaus and Vladimír Mečiar; the latter did it for his own benefit. Chauvinistic nationalists took control, massive corruption and fraud occurred, and Slovakia quickly became the black hole of Europe both politically and economically.

A turbulent period followed: car bombings, the kidnapping of the president’s son, and other unbelievable events. Mečiar showed clear authoritarian tendencies, and autocracy threatened Slovakia. But in 1998, he was defeated in elections—a moment I consider as important as the Slovak National Uprising during WWII.

We confirmed our desire to be part of Europe, and in 2004 we joined the EU. That was the last time history ended—and this time, truly and definitively. Well, at least or now.

It is going to be like this forever

1918, 1939, 1945, 1948, 1968, 1989, 1993, 2004. Eight ends of history in less than a century, each supposed to be forever. Since the last one, twenty-one years of peace and stability. Yet there’s a feeling that another end of history is coming.

My grandmother is proof that a person doesn’t have to do anythinf and the end of history will still come. That’s both good and bad news. Bad if you live in a democracy, good if you live in a dictatorship. History has never truly ended and doesn’t seem to be ending now. In this sense, the current period is neither exceptional nor unique.

I remember how, after the Velvet Revolution in 1989, we felt as Czechoslovak citizens—we finally did it, we got our freedom, all we have to do now is enjoy it. But then Czechoslovakia broke up, Slovakia nearly became an autocracy, and that freedom didn’t bring what many expected.

I also remember how Slovaks felt after joining the EU in 2004—we finally did it (again), it’s official, we’re part of the most developed part of the world. All we have to do now is just be and not mess it up. But today, Europe is facing Russian expansionalism, its own internal problems, and as if this wasn’t enough, our own prime minister Robert Fico is pulling Slovakia away from Europe. Turns out we can never just be. And we also messed it up quite a bit.

In 1989 and 2004, we were firmly convinced this would last forever—as we always had been before. But that was never really true, not just in post-communist Europe but anywhere.

A pro-Russian government in a pro-European country

It’s 2025. Two years ago, in autumn 2023, early parliamentary elections in Slovakia narrowly brought victory to Robert Fico’s Smer party. It then formed a nationalist, pro-Russian coalition with Hlas (which split from Smer earlier) and the Slovak National Party.

Robert Fico has shaped Slovak politics for over twenty years. Since 2006, he’s won five elections and is now serving as prime minister for the fourth time. Whether he will govern again or be defeated has been the leitmotif of every election for about fifteen years.

In the 1980s, Fico was a Communist Party member, later founding Smer. He started as a modern Blairite leftist, then became a pro-European left-wing populist, but today he is far-right, anti-European, and pro-Russian. Whereas before his victories meant a routine transfer of power, another Fico triumph could now decide Slovakia’s future—especially amid current geopolitics.

For the purposes of this article, one statement and one question matter: Statement—Slovakia has a pro-Russian government. Question—are its citizens pro-Russian then?

Foreign policy attitudes have been continuously studied for three decades, and the answer, clearly, is no. Slovakia is pro-European: according to Globsec, 72% supported EU membership in spring 2024. According to Eurobarometer in early 2025, 86% support the euro. As for geopolitical orientation—should Slovakia belong to the West, the East or somewhere inbetween—the West has been growing steadily and the center is declining, especially after Russia invaded Ukraine. About 15% support Slovakia belonging to the East, forming a marginal minority.

A glorious opportunity wasted

The logical question is this: why did pro-Russian Robert Fico win if the people themselves aren’t pro-Russian? The answer is banal: whenever his opponents came to power in the past two decades, they performed catastrophically.

Simple statistics: Fico is prime minister for the fourth time and his government never collapsed and always served the full term, including during huge political turmoil after the murder of journalist Ján Kuciak and his fiancée Martina Kušnírová. The “opposite” government last finished its term in 2002; that is almost quarter of a century ago. Following their rule, early elections had to be held in 2006, 2012, and 2023—when two governments fell.

Especially the last government before Fico performed tragically. In 2020, populist Igor Matovič won on an anti-Fico wave and even formed a coalition holding a constitutional majority.

Soon, however, COVID stuck, followed by internal conflicts, the premier’s histrionics, an economic crisis, the war in Ukraine. Using all of this was an increasingly aggressive Fico, who adopted all anti-system positions, including opposing COVID vaccinations, indirectly causing thousands of deaths.

Thanks to the trully awful performance of the anti-Fico coallition, the constitutional majority vanished into thin air after two years, two governments collapsed under curcimstances that are better not described and the government’s approval ratings dropped to 12%. Virtually no one trusted them at all.

This was a huge chance that ended in a huge defeat. The people distrusted and despised the government, its chaos and incompetence, and Fico managed to embody this sentiment with a slogan promising the end of chaos. And he won.

People did not vote for pro-Russian Robert Fico because of his foreign policy but because of the catastrophic domestic performance of the previous government. Foreign policy orientation didn’t matter; they wanted the chaos to be over and didn’t ask for much. All they wanted was to wake up in the morning safe in the knowledge things are roughly the same as last night. Under Igor Matovič, this was often not the case.

It really is very banal. It’s 2025, and Robert Fico rules Slovakia for the fourth time. He openly aims to build some kind of autocracy, treats Europe as an enemy and recently visited the Kremlin. What a glorious opportunity wasted

The question is what this means not only for Slovakia but for the entire region, which repeatedly finds itself at the end of history.

A window of opportunity

Slovakia cannot relocate itself; it will always have the same neighbors; the same applies to the whole region. Today it’s part of the Western world, and I lean towards the interpretation that it succeeded during a small window of opportunity when first the Soviet Union, then Russia, were too weak to push their geopolitical interests.

We used this window of opportunity, but the question is whether we used it well enough. Independent countries emerged and integrated into Euro-Atlantic structures. But are these countries strong enough? Have they managed to build strong ties to the West? Are they strong enough internally? Have they managed to build strong institutions, systems, mechanisms?

The window of opportunity is slowly closing, and regarding Slovakia, I think the answer is no. Was it even possible at all? How much can realistically be done in three decades? To that, I don’t have an answer.

That doesn’t mean all is lost—this article’s thesis is that it never is—but it does mean the situation is extremely serious. Even more so as the global order and security architecture are shaking, and all modern democracies face all kinds of different problems.

My parents lived much of their lives under communism and faced the difficult post-communist transition; that doesn’t apply to me. My generation remembers the Velvet Revolution, grew up fighting Vladimír Mečiar, and considers EU accession a generational success.

I grew up in a world that was supposed to only ever get better. I was raised in the belief that history was linear and always moved forward. Global events seemed to confirm this. Personally, I was told effort is rewarded—and it largely was, with en emphasis on the past tense.

Today, that hardly applies anymore: we can hardly say things will only get better. History is not linear and doesn’t always move forward—it never was, and we were mistaken. Younger generations have a far less optimistic view of the future than I once did, and rightly so: they see that effort doesn’t automatically get rewarded, and the future doesn’t look bright in far too many aspects.

I think the question “what now, after the end of history?” arises from this. But I think a simpler question is: what now?

An unusual period of peace

Every generation has its geopolitical turning points. For me, these were the fall of communist regimes in 1989, the fall of the Twin Towers in 2001, and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The first meant freedom and integration into the West; the second marked the start of the opposite process. The Russian attack on Ukraine is a clear sign that countries like Slovakia and people like me face imminent danger—the victim this time is a neighboring country.

At risk is the system and the world I want to live in, based on values I share. It seems unable or unwilling to defend itself sufficiently—or both. Liberal democracy, or democracy itself, is in retreat worldwide, and Slovakia’s current developments are part of this global trend. Changes in geopolitical and security architecture are inevitable. The world will change just like it always does.

A country like Slovakia has little choice and depends on membership in Western structures; quoting Shakespeare, it’s a matter of to be or not to be. As a result, such shifts are bad news. Worse yet, the current Slovak government welcomes these changes, distances itself from its natural allies, and favours a “multidirectional” foreing policy. The thing is, somehow it always ends up in the Kremlin.

Thus, the current Slovak government poses an acute threat to democratic, pro-European Slovakia. In broader terms, another end of history is underway, and we were wrong: the last thirty-five years were not a given. It was rather an unusual, long period of peace, stability, and prosperity caused mainly by the Soviet Union and Russia lacking the strength to push their interests. This is no longer the case.

If we accept that a historical shift is happening—which seems reasonable—we come to the question of how to defend ourselves.

Something could still have been done back then

It may sound banal, but governance performance matters; Slovakia saw this in 2020–2023, when Igor Matovič’s coalition governed disastrously and people again voted for Robert Fico.

This means that when an opportunity arises, it must be handled carefully and responsibly: if democratic, pro-western and liberal (in the widest sense) forces are in power, they must focus on maintaining trust, finishing their term, and not forgeting what the risks of failure entails. In Slovakia, it entailed Fico’s return and a turn toward Russia. Things really can happen very quickly.

Furthermore, domestic politics always have international implications: Slovakia isn’t the most important country in Europe, not by far, but in a politically integrated world, even poor governance in one country may lead to wide European effects. Consensus becomes fragile, joint steps harder, and, worst of all, this weakness is exposed at a time of existential threat.

Other, wiser people will surely come up with many more and wiser answers, but I will add one more word that you probably wouldn’t expect in a text like this: the older I get, the more importance I think empathy is, both on an individual and societal level.

Empathy means trying to understand that today, we live in a complex world that some people may find difficult to comprehend and adjust to. For them—especially for the older generation—everyday life may as well be a neverending series of problems they aren’t able to deal with.

We also live in an interconnected world but at the same time, many people suffer from deep loneliness and a sense of alienation. They are or feel alone, left behind and more often than not, it is true.

We need to understand that not everyone can perceive the developments of the last thirty-five years as purely positive and that there are also those who failed to benefit from them. In our geographical region, the economic crisis of 2008 is hardly given any significance, but on a global scale, it was precisely then that doubts about the system we live in—namely liberal democracy and globalization—first arose.

It is precisely these people—those who objectively found themselves on the periphery of events, or at least feel that way—whom Robert Fico has been focusing on in Slovakia. He is not empathetic, but he has successfully faked empathy for decades; he looked like he cared. “You matter”, he told them Since no one else addressed these people, and many even questioned or ridiculed their situation, he has long appealed to them. This is one of the main feasons he is now prime minister for the fourth time.

Empathy will help us understand where all these feelings come from. If we recognize them as legitimate and understand them, then we can work with them. If we can work with them, we can—in some form—save the world we live in. We urgently need empathy as people and as societies; the sheer number of dissatisfied people is indeed telling us something.

History is constantly changing, especially where we live. And it can easily head again in a direction we will not like at all. I myself lived in communist Czechoslovakia, democratic Czechoslovakia, and now I live in Slovakia. I experienced 1989, I witnessed Vladimír Mečiar’s defeat in 1998 when the future of Slovakia was truly decided, and I also lived through the country’s entry into the European Union.

I do not want to experience what my grandmother did, and could certainly do without further historical upheavals. Yet today, both I personally and the whole of Slovakia find ourselves in a situation that we might look back on in five years as a moment when something could still have been done. I believe that the Western world, or if you will, liberal democracy, is in a very similar situation.

History keeps ending over and over again and it also never ends; sometimes that is good, sometimes bad. Slovakia today is a sobering example of this.